Education in the UK

Preliminary pages

Introduction, Contents, Preface

Chapter 1 Up to 1500

Beginnings

Chapter 2 1500-1600

Renaissance and Reformation

Chapter 3 1600-1660

Revolution

Chapter 4 1660-1750

Restoration

Chapter 5 1750-1860

Towards mass education

Chapter 6 1860-1900

A state system of education

Chapter 7 1900-1923

Secondary education for some

Chapter 8 1923-1939

From Hadow to Spens

Chapter 9 1939-1945

Educational reconstruction

Chapter 10 1945-1951

Labour and the tripartite system

Chapter 11 1951-1964

The wind of change

Chapter 12 1964-1970

The golden age?

Chapter 13 1970-1974

Applying the brakes

Chapter 14 1974-1979

Progressivism under attack

Chapter 15 1979-1990

Thatcher and the New Right

Chapter 16 1990-1997

John Major: more of the same

Chapter 17 1997-2007

Tony Blair and New Labour

Chapter 18 2007-2010

Brown and Balls: mixed messages

Chapter 19 2010-2015

Gove v The Blob

Chapter 20 2015-2018

Postscript

Timeline

Glossary

Bibliography

Organisation of this chapter

Background

Thatcher's three terms

Neo-liberalism

The 'New Right'

Education Secretaries

Mark Carlisle

Keith Joseph

Kenneth Baker

John MacGregor

1979-83 Preparing the ground

Budget cuts

The end of comprehensivisation

Selection

Assisted Places Scheme

Confrontation

Parent power

Education vouchers

1980 Education Act

1981 Education Act

The curriculum

DES publications

HMI publications

Schools Council contribution

Inside the primary classroom

Youth Training Scheme

TVEI

Microelectronics education

School effectiveness

The teachers

1983 White Paper

Reports

1981 Rampton: West Indians

1982 Cockcroft: Maths

HMI surveys

Secondary education

Education 5 to 9

9-13 middle schools

Higher education

1983 Education (Fees and Awards) Act

1983-1987 Increasing the pressure

Second term priorities

Differentiation

Joseph's aims

Other Tory views

Circular 8/83

Parent power

1984 Green Paper

1985 White Paper

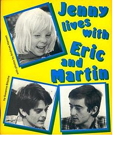

Sex education

1986 Education (No. 2) Act

The curriculum

General Certificate of Secondary Education

The Curriculum from 5 to 16

The teachers

The Schools Council

ACSET

Teachers' pay and conditions

The local authorities

Education Support Grants

Rate-capping

Specific grants for in-service training

Publication of political material

Vocational education

1985 Swann Report: Ethnic minorities

Growing anxiety

Oxford and Thatcher

1985 Jarratt Report

Jackson Hall's warning

The end of Joseph

Baker's first year

City Technology Colleges

National core curriculum

Local management of schools

Higher education

Opting out

1987-1990 Taking control

Conservative election manifesto

Section 28

Towards the Education Reform Act

The National Curriculum

Task Group on Assessment and Testing

Subject working groups

The Education Reform Bill

Second reading

Committee stage

The bill in the Lords

Final debates

1988 Education Reform Act

Summary of the Act

Reaction

After the Act

National Curriculum

Religious education

Local management of schools

Grant-maintained schools

City Technology Colleges

ILEA

Reports

1988 Kingman: English

1988 Higginson: A Levels

1989 Elton: discipline

1990 Rumbold: early years

Beyond Baker

John MacGregor

GM schools in Scotland

Student loans

Conclusions

References

| |

Education in the UK: a history

Derek Gillard

first published June 1998

this version published May 2018

© copyright Derek Gillard 2018

The right of Derek Gillard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. This work is reserved from text and data mining in accordance with Article 4(3) Directive (EU) 2019/790.

What does that mean?

It means you may download this work and/or print it for your own personal use, or for use in a school or other educational establishment, provided my name as the author is attached. But you may not publish it, upload it onto any other website, or sell it, without my permission, and it is not to be used in the training of AI systems.

A printer-friendly version of this chapter can be found here.

Citations

You are welcome to cite this work. If you do so, please acknowledge it thus:

Gillard D (2018) Education in the UK: a history education-uk.org/history

References

In references in the text, the number after the colon is always the page number (even where a document has numbered paragraphs or sections).

Documents

Where a document is shown as a link, the full text is available online.

© Crown copyright material is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen's Printer for Scotland.

Chapter 15 : 1979-1990

Thatcher and the New Right

Background

Thatcher's three terms

Margaret Thatcher (1925-2013) (pictured) had replaced Edward Heath as Conservative leader in February 1975, marking a decisive shift to the right for the party. Margaret Thatcher (1925-2013) (pictured) had replaced Edward Heath as Conservative leader in February 1975, marking a decisive shift to the right for the party.

With the election of her first administration on 3 May 1979, neo-liberalism became the dominant force in British politics. Her government's policies 'accelerated the closing down of unprofitable industries and promoted a profound social and economic restructuring' (Jones 2003:107). In just four years, Britain lost a quarter of its manufacturing capacity (Jones 2003:107-8).

The incidence of poverty increased dramatically: the number of those receiving Supplementary Benefit rose from 4.4m in 1979 to 7.7m in 1983; those below the Supplementary Benefit level increased from 2.1m to 3.3m. 'By any reasonable criterion, some nine million, or one-sixth of the population, were living in poverty ... and the numbers were to increase' (Morris and Griggs 1988:11).

By 1982 the Thatcher government was highly unpopular. Soaring inflation and a massive increase in unemployment made it seem unlikely that she would win a second term. She needed a miracle. Fortunately for her, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands and she was able to play the part of heroic war leader in the Falklands War between March and June 1982. This, coupled with the unpopularity of the left-wing Labour leader Michael Foot, and the defection of some Labour supporters to the newly-formed Social Democratic Party, resulted in a Tory landslide in the general election on 9 June 1983. With her Commons majority increased from 43 to 144, Thatcher was able to take her reforms further.

Her second administration is most notable for its determination to destroy Britain's coal industry. The miners' response was a year-long strike which was ruled illegal in September 1984 because there had been no national ballot. Violence broke out between pickets and the police, miners' families were reduced to relying on soup kitchens to survive, and the strike collapsed. The destruction of the coal industry continued, with former mining areas suffering appalling levels of poverty.

Thatcher won a third term in office at the general election on 11 June 1987. Her majority of 102, though reduced, was nevertheless substantial, and the 'iron lady' felt powerful enough to push ahead with some unpopular policies, most notably the introduction of a form of poll tax. Riots ensued, her colleagues deserted her, and she was ousted from office in November 1990.

Neo-liberalism

Thatcher's neo-liberal policies affected not only industry and commerce but also public services.

Conservative legislation sought to drive neo-liberal principles into the heart of public policy. An emphasis on cost reduction, privatisation and deregulation was accompanied by vigorous measures against the institutional bases of Conservatism's opponents, and the promotion of new forms of public management. The outcome of these processes was a form of governance in which market principles were advanced at the same time as central authority was strengthened (Jones 2003:107).

The origins of this policy can be traced back to the establishment in 1955 of the Institute of Economic Affairs, a right-wing think-tank which, during the 1970s, had 'worked tirelessly to persuade the Conservative Party to abandon the post-war welfare consensus and embrace social and educational policies based on nineteenth-century free-market anti-statism' (Chitty 2009a::47).

These ideas were promoted by Stuart Sexton, adviser to Thatcher's first Education Secretary, Mark Carlisle. In Evolution by choice, his contribution to the last of the Black Papers in 1977, he had sketched out 'a new system for secondary education':

Obviously we get rid of the 1976 Education Act for a start. We remove all other political constraints and directions which seek to distort the pattern of educational supply and demand. We have to assume that the politicians keep their fingers out of it, apart from laying down the framework within which variety and diversity can abound in accordance with the aspirations and abilities of the children (Sexton 1977:86).

Such a system would be based on 'absolute freedom of choice of application' (Sexton 1977:87). Local authorities would no longer allocate children to schools: 'The parent should be able to apply to any secondary school; there should be no zones, no catchment areas' (Sexton 1977:87). Where a school was oversubscribed it would select its students on the basis of 'ability and aptitude' (Sexton 1977:87). The educational market would not be entirely unregulated: there would be an independent inspectorate, 'minimum standards and a minimum curriculum' (Sexton 1977:86).

The exercise of parental choice is the key. The very exercise of that choice, and the response to that choice, will produce the schools which the parents want and the children need. The comprehensives will evolve from the present mediocre sameness imposed by the bureaucracy towards the diversity demanded by the parents. They will be different, school to school, country to town, just as children are different. They will be good schools or they will close (Sexton 1977:88-9).

Sexton's theme was taken up by an 'ever-growing number of right-wing think-tanks with small but interlocking memberships' which 'bombarded' ministers with policy ideas 'ideologically driven by commitment to the market and to privatisation' (Benn and Chitty 1996:12).

The 'New Right'

As Clyde Chitty has noted, the 'New Right' was not a single homogenous entity: it encompassed a range of groups which could broadly be described as 'neo-liberal' or 'neo-conservative'. There was thus

a paradox at the very heart of New Right philosophy. ... Different meanings are attached to these two terms and they are given different weight by different factions within the New Right, but if the New Right has a unity and can be distinguished from previous right-wing groupings, what makes it special is the unique combination of a traditional liberal defence of the free economy with a traditional conservative defence of state authority.

This combination of potentially opposing doctrines means that New Right philosophy has contradictory policy implications and the ambiguity owes much to a basic division between those, on the one hand, who emphasise the free economy, often referred to as the neo-liberals, and those on the other who attach more importance to a strong state, the so-called neo-conservatives (Chitty 1989:212).

Thatcher's education policies were a combination of the two. Thus the imposition of the National Curriculum could be seen as an example of neo-conservatism; while giving parents the right to choose schools and allowing schools to opt out of local authority control were manifestations of neo-liberalism.

Education Secretaries

The Secretaries of State for Education and Science during this period were:

| 5 May 1979 | Mark Carlisle (1929-2005) |

| 14 September 1981 | Sir Keith Joseph (1918-1994) |

| 21 May 1986 | Kenneth Baker (1934- ) |

| 24 July 1989 | John MacGregor (1937- ) |

Mark Carlisle

The son of a cotton merchant, Carlisle was educated at Radley College Abingdon, read Law at Manchester University, and entered Parliament in 1964 as MP for Runcorn in Cheshire. He served in a number of junior ministerial positions in the Home Office before being appointed shadow education secretary in 1977, and then education secretary in Thatcher's first administration. He felt somewhat ill at ease in the post, freely admitting that 'I had no direct knowledge of the state sector either as a pupil or as a parent' (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:55).

On the liberal wing of the Tory party - 'moderate and essentially pragmatic' (Chitty 2009a::48) - he was 'distinctly out of sympathy with the views of right-wing Conservatives on education' and 'worked quietly to dilute the impact of the Radical Right on the Party's education policy' (Knight 1990:138). In particular, he regretted the promotion of Rhodes Boyson within the DES (Department of Education and Science). In a letter dated 18 April 1985, he told Christopher Knight:

It was my preference to put Lady Young in charge of schools and not Boyson. I thought Boyson was too over-zealous on schools. When I took over in 1979 the education system was still in a fair amount of disarray and I did not want Boyson to upset the teachers. I wanted a conciliatory rather than provocative approach (quoted in Knight 1990:138).

Carlisle's list of priorities 'did not include vouchers or any of the other proposals favoured by the educational radical right for privatising parental choice of school' (Knight 1990:142). The only policy for which he sought Thatcher's approval was the Microelectronics Education Programme, which was implemented through the Department of Industry in 1980-81 (details below).

His main interest was in raising standards generally, as he told the 1979 Conservative Party Conference:

What we mean when we talk about raising standards in education is raising the standards of achievement for all, raising the standards of literacy and numeracy, raising the quantity and quality of mathematicians, scientists and linguists, raising the standards of behaviour and discipline in our schools. If we are to achieve those improved standards we shall do it only by the pursuit of excellence. The Conservative Party is still the party of one-nation and its education policy has to be the policy of one-nation (quoted in Knight 1990:142).

One of Carlisle's problems was the attitude of Thatcher herself, as he explained to Peter Ribbins:

She didn't much like teachers, and she didn't seem to like civil servants she encountered at the DES. This did not make it any easier for me. I found the pressures very hard, very exacting (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:64).

He was aware that Thatcher did not have a high opinion of him as education secretary, but 'I never understood what it was that she was unhappy about' (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:66). He acknowledged, however, that his decision to allow Thameside to go comprehensive 'clearly did not enamour me to the Tory party' (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:66-7).

Keith Joseph

Joseph was from a wealthy and influential Jewish family - his father was head of the construction firm Bovis. He was educated at Harrow and Magdalen College Oxford, and entered Parliament in 1956 as MP for Leeds North East. Joseph was from a wealthy and influential Jewish family - his father was head of the construction firm Bovis. He was educated at Harrow and Magdalen College Oxford, and entered Parliament in 1956 as MP for Leeds North East.

On the right wing of the Tory party, he founded (with Margaret Thatcher and Alfred Sherman) the Centre for Policy Studies in 1974 and wrote its first publication Why Britain needs a Social Market Economy. He had controversial views on the state education system. In an interview with Stephen Ball, he said:

We have a bloody state system I wish we hadn't got. I wish we'd taken a different route in 1870. We got the ruddy state involved. I don't want it. I don't think we know how to do it. I certainly don't think Secretaries of State know anything about it. But we're landed with it. If we could move back to 1870, I would take a different route. We've got compulsory education, which is a responsibility of hideous importance, and we tyrannise children to do that which they don't want, and we don't produce results (quoted in Ball 1990:62).

Joseph's educational philosophy was, by his own account, firmly-rooted in the thinking of the original One Nation group of Tory MPs. In June 1986 he told Christopher Knight:

Like Angus Maude, I was a One Nation group member in 1956. We believed levelling in schools had to stop and that excellence (discrimination) had to return. Our key perception was differentiation. We equated the stretching of children, at all levels of ability, with caring. Our aim was to achieve rigour in the school curriculum. Later, I was much influenced by Maude's views in The Common Problem, and the Black Papers. The Black Papers responded to a strong national perception, that there was a vast gap between what people received and what people needed in education. Because of the fall in the birth-rate and school rolls I decided, when I took office in 1981, to go for quality not quantity. For too long popular high expectations of education had led to popular disappointments. Large sections of the nation were eager for improvements. We wanted to satisfy the thirst for good education (quoted in Knight 1990:152).

Joseph believed that 'a market solution could only proceed (and succeed) in conjunction with a paternalistic Inspectorate' (Knight 1990:152); that there was a need for better value for money in the national investment in education; and that the Conservative Party should 'implement policies to foster excellence and elites rather than equality of condition' (Knight 1990:154). He argued for a return to traditional classroom teaching styles, telling the 1981 Conservative Party Conference:

I welcome the fact that the mixed-ability tide seems to have ebbed. Mixed-ability teaching calls for very rare teaching skills if it is to benefit every child in a non-selected class (quoted in Knight 1990:155).

Joseph had a low opinion of the educational establishment, and of the teacher unions in particular. He told Clyde Chitty:

You don't understand what an inert, sluggish, perverse mass there is in education. The teacher unions were ... perverse, perverse; except for one or two of them, they didn't concern themselves with quality, or didn't appear to. I had union leaders make half-hour speeches without mentioning children. It was a producer lobby, not a consumer lobby (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:80).

His four-and-a-half years in office would prove to be 'a disastrous period for education, culminating in a crisis almost reaching the proportions of a Greek tragedy - and having similar characteristics' (Simon 1991:488).

Kenneth Baker

The son of a civil servant, Baker was educated at St Paul's School and read history at Magdalen College Oxford. He served as MP for Acton (from 1968), then St Marylebone (from 1970), and for Mole Valley in Surrey (1983-97). The son of a civil servant, Baker was educated at St Paul's School and read history at Magdalen College Oxford. He served as MP for Acton (from 1968), then St Marylebone (from 1970), and for Mole Valley in Surrey (1983-97).

A 'liberal-moderate Tory' (Knight 1990:184), Baker had been Parliamentary Private Secretary to Edward Heath (1974-75); Heath's campaign manager during the 1974-75 party leadership contest; Minister for Information Technology (1981-84); and Environment Secretary (1985-86).

He is principally remembered for the controversial Education Reform Act of 1988, sometimes referred to as 'the Baker Act'.

In November 1990 he was appointed Home Secretary by Thatcher's successor John Major, and in 1997 he became Baron Baker of Dorking.

John MacGregor

MacGregor was educated at Merchiston Castle School, and read economics and Law at the University of St Andrews and King's College London. He became a journalist, and then worked for the merchant bank Hill Samuel. MacGregor was educated at Merchiston Castle School, and read economics and Law at the University of St Andrews and King's College London. He became a journalist, and then worked for the merchant bank Hill Samuel.

First elected to Parliament in 1974 as MP for South Norfolk, he served in various junior ministerial positions before being appointed Chief Secretary to the Treasury in 1985, then Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food in 1987.

His period as education secretary was short (16 months) and unremarkable. Interviewed by Peter Ribbins in September 1994, he said:

I came to the view very quickly that Kenneth Baker had carried through the major reforms, particularly in the school sector, which were necessary, and that my job was to make them work (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:127).

He held traditional Tory views on educational issues, telling Ribbins, for example, that

I have always been critical of the way educational thinking developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s under the influence of the teacher training institutions. ... I feel that some of the ideas about child-centred learning which were so influential during these years have a lot to answer for with regard to the lowering of standards which has taken place in too many of our primary and secondary schools (quoted in Ribbins and Sherratt 1997:129).

Ribbins did not ask him to provide evidence for the 'lowering of standards'.

MacGregor became Leader of the House of Commons in 1990 and then Secretary of State for Transport in 1992.

1979-1983 : Preparing the ground

Clyde Chitty has suggested that

for at least the first seven years of its existence, the new Conservative government was prepared to operate largely within the terms of the educational consensus constructed by the Labour leadership of 1976 (Chitty 1989:194).

The 1979 Conservative election manifesto contained no surprises: a brief section on 'Standards in education' declared that

We will halt the Labour government's policies which have led to the destruction of good schools; keep those of proven worth; and repeal those sections of the 1976 Education Act which compel local authorities to reorganise along comprehensive lines and restrict their freedom to take up places at independent schools.

We shall promote higher standards of achievement in basic skills. The Government's Assessment of Performance Unit will set national standards in reading, writing and arithmetic, monitored by tests worked out with teachers and others and applied locally by education authorities. The Inspectorate will be strengthened. In teacher training there must be more emphasis on practical skills and on maintaining discipline (Conservative manifesto 1979).

This was followed by two paragraphs on 'Parents' rights and responsibilities':

Extending parents' rights and responsibilities, including their right of choice, will also help raise standards by giving them greater influence over education. Our Parents' Charter will place a clear duty on government and local authorities to take account of parents' wishes when allocating children to schools, with a local appeals system for those dissatisfied. Schools will be required to publish prospectuses giving details of their examination and other results.

The Direct Grant schools, abolished by Labour, gave wider opportunities for bright children from modest backgrounds. The Direct Grant principle will therefore be restored with an Assisted Places Scheme. Less well-off parents will be able to claim part or all of the fees at certain schools from a special government fund (Conservative manifesto 1979).

Budget cuts

The Thatcher government's first budget called for immediate savings in education amounting to between £250m and £400m; and plans were made for a further 3.5 per cent cut in the education budget in 1980-81 (Simon 1991:479).

In addition, the 1980 Local Government, Planning and Land Act (13 November) introduced new arrangements for the financing of local government, involving changes to the Rate Support Grant. These were so complex that 'few fully understood the proposals' (Simon 1991:481), but it was generally understood that they were another means of cutting expenditure. Writing in Education (1 August 1980), Jack Springett, Education Officer of the Association of Metropolitan Authorities, warned that the new system placed 'unlimited powers in the hands of ministers' and undermined local authorities' responsibilities for decision-making (quoted in Simon 1991:481).

The government commissioned a series of departmental studies aimed at achieving savings and increasing efficiency and effectiveness. As part of the 'Rayner Review' (it was overseen by Sir Derek Rayner (1926-1998) of the Cabinet Office), the DES and the Welsh Office were asked, in December 1980, to conduct a review of HM Inspectorate.

Published in 1982, the Study of HM Inspectorate in England and Wales suggested that there was little scope for cuts in HMI staffing:

The present complement of 430 should be regarded as a maximum. It would be feasible, although not desirable, to accept a reduction in complement to 420. Any further reduction would carry penalties for the effectiveness of the Inspectorate and put many of the recommendations for improvement proposed in the study beyond reach (DES/Welsh Office 1982:95).

Meanwhile, HMI reports showed that a third of schools were in poor condition; half of local authorities had radically reduced their repair and maintenance budgets; and one shire county had undertaken no interior decoration of its schools for fifteen years. Further cuts would clearly be very damaging.

Despite these warnings, the White Paper The Government's Expenditure Plans 1981-82 to 1983-4 (10 March 1981) proposed an overall reduction of 7 per cent in education, with capital spending planned to fall by more than 30 per cent.

With the severe cut imposed on capital expenditure the basis was now laid for the continuous deterioration of the fabric of schools and colleges which characterised the 1980s (Simon 1991:480).

Carlisle (like other ministers) attempted to resist the cuts, and privately warned colleagues that a reduction of up to 7 per cent would seriously damage educational standards. Publicly, however, he 'gave no indication of his misgivings about the implications for education of Mrs Thatcher's economic experiment' (Knight 1990:137).

On top of the cuts to school and local authority budgets, in July 1981 the government announced drastic cuts to university budgets. The result was widespread protests by teachers and students.

The end of comprehensivisation

The government's immediate aim - to 'get rid of the 1976 Education Act', as Sexton had put it - was effected within three months of the election.

Selection

The 1979 Education Act (26 July) contained just one provision: it repealed Labour's 1976 Act and gave back to local education authorities the right to select pupils for secondary education at the age of eleven. It thus marked the end of comprehensivisation as government policy.

Chaos ensued in some local authorities. Tory-controlled Bolton council decided (by one vote) to scrap its comprehensive scheme, which meant that 3,000 children suddenly had to take eleven-plus tests. When Labour regained control four years later, Bolton finally went comprehensive. Meanwhile, nearby Tameside Council, now Labour-controlled, voted to reverse Tory policy and implement its own, earlier comprehensive plan. Carlisle refused to sanction it, but legal action resulted in a victory for the council.

Thus comprehensivisation continued under Carlisle and, by 1982, DES figures showed that 89.3 per cent of pupils in maintained secondary schools were in comprehensives (Simon 1991:482). As Caroline Benn pointed out, however, the real figure was much lower. Less than three quarters of all secondary age pupils were in comprehensives, she said,

and that is before we start discounting the bogus comprehensives and all those which are creamed by selective or fee-paying schools. In fact, the 'genuine' uncreamed comprehensive population is probably only about 50% of the country (Benn 1980:40).

Furthermore, there was still selection of pupils within comprehensive schools, between the General Certificate of Education (GCE) and Certificate of Secondary Education (CSE) streams. Carlisle, who at first rejected the idea of a single unified exam system, was persuaded to change his mind, but it would be 1988 before the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) came into being (details below).

In the event, attempts to reintroduce or extend selection in Berkshire, Wiltshire, Redbridge, Cumbria and Solihull all failed as a result of strong local opposition: the Tories had underestimated the popularity of comprehensive schools. The 'Solihull adventure', as Brian Simon calls it, was particularly significant:

Solihull had opted, and in a very clear manner, to retain its comprehensives, and no more was heard of the original project. Just after the return of a Tory government, and in the area of a well established Tory authority, a clear and precise public test brought out very dramatically the degree of support existing for local comprehensive systems (Simon 1991:499).

Assisted Places Scheme

A year later, the government introduced its Assisted Places Scheme: section 17 of the 1980 Education Act (3 April) provided public money to pay for 30,000 children to go to private schools.

The scheme - costing £6m in the first year, £70m when fully operational - would be paid for out of the general education budget: in other words, from resources that would otherwise have been available to local authorities and their schools.

The former Tory Prime Minister, Edward Heath, was not in favour, believing that

a policy of extracting the highest fliers from the state sector in significant numbers would have an unacceptably debilitating impact on those who remained (Heath 1998:82).

He was dismayed that nobody had spared a thought

for the youngsters who would have to be the first to endure this experiment in social engineering, nor for the effects on the schools from which they would make an exodus. After all, these youngsters were the leaders in embryo of their houses, in work and in sport, in music and debate, and their loss would lower the standards of their schools all round (Heath 1998:81-2).

Heath also believed, as he had in 1940, that the main motivation behind proposals for state bursaries was to support private schools known to be in financial difficulties.

Confrontation

As unemployment reached 2.6m during the summer of 1981, riots broke out across the country. Ministers who would not support Thatcher's confrontational style were replaced in a Cabinet reshuffle in September. Carlisle was 'unceremoniously sacked', his place taken by Thatcher's monetarist guru, Keith Joseph. 'This reshuffle marked the beginning of Thatcher's real ascendancy within the Cabinet and party' (Simon 1991:482).

The appointment of Joseph was a signal that school reform was moving up the government's agenda. A long-time advocate of free market ideas, Joseph found himself

commanding an apparatus that was now increasingly involved in specifying the everyday practice of schools. ... Joseph, like the ministers who succeeded him, organised in the name of 'effective education' a vast new complex of regulations and regulators that would measure and direct the processes and outcomes of schooling (Jones 2003:115).

The government's twin aims - as advocated by the Centre for Policy Studies and the Downing Street Policy Unit - were to make the education system more responsive to the needs of industry and more susceptible to market forces.

To achieve these aims, Thatcher and Joseph set about confronting the 'education establishment' - the teachers and their unions, the local authorities, the training institutions, and national and local inspectors and advisors. Initially, there was action on two fronts:

- parent power - giving parents more control over schools; and

- the curriculum - increasing central government's influence over what was taught in schools.

In Thatcher's second term there would be action in two other areas:

- the teachers - controlling their training and development and restricting their role in curriculum development; and

- the local education authorities - reducing their power to subvert central government policies.

Parent power

Education vouchers

The notion of the education voucher, enabling parents to choose any school within or outside the state system, had been around for a long time: Milton Friedman, then a relatively little-known economist at the University of Chicago, had advocated it in the 1950s. In Britain, vouchers had been promoted enthusiastically by Tory MP Rhodes Boyson in the last two Black Papers (1975 and 1977 - see the previous chapter).

Joseph's education team, argues Knight, comprised representatives of the two major schools of right-wing educational thought - the 'centralisers' and the 'decentralisers'.

It is important to note this division because ... although Joseph's team was united in its broad support for raising educational standards, it displayed less agreement over precise schemes to improve the mechanics of parental choice. Significantly, each grouping was distinguished by its varying degrees of support for, and opposition to, the education voucher (Knight 1990:158).

The decentralisers, who advocated the voucher, included Rhodes Boyson and Stuart Sexton. The centralisers, who were opposed to the voucher, included Joseph himself. He had initially been sympathetic to vouchers but, from 1981, was 'sceptical of their administrative practicality' (Knight 1990:158). At the 1981 Conservative Party Conference, he was loudly applauded when he said

I personally have been intellectually attracted to the idea of seeing whether eventually, eventually, a voucher might be a way of increasing parental choice even further ... I know that there are very great difficulties in making a voucher deliver - in a way that would commend itself to us - more choice than the 1980 Act will, in fact, deliver. It is now up to the advocates of such a possibility to study the difficulties - and there are real difficulties - and see whether they can develop proposals which will really cope with them (quoted in Chitty 1989:183).

In response to requests from pressure groups for further information, Joseph asked his civil servants to prepare a paper on the feasibility of a voucher scheme. This memorandum, dated December 1981, stated that the Secretary of State had 'no plans for the general introduction of a voucher scheme' (quoted in Chitty 1989:184).

Despite opposition from DES officials, who were 'anxious to see the whole idea quietly dropped' (Chitty 1989:184), Joseph continued to make speeches in support of vouchers, while never committing the government to implementation.

In the autumn of 1983, however, he told the Conservative Party Conference: 'the voucher, at least in the foreseeable future, is dead' (quoted in Chitty 1989:184).

He set out his reasons for coming to this decision in a written Commons statement in June 1984:

I was intellectually attracted to the idea of education vouchers because it seemed to offer the possibility of some kind of market mechanism which would increase the choice and diversity of schools in response to the wishes of parents acting as customers. In the course of my examination of this possibility, it became clear that there would be great practical difficulties in making any voucher system compatible with the requirements that schooling should be available to all without charge, compulsory and of an acceptable standard. ...

I concluded that the difficulties which would arise from the many and complex changes required to the legal and institutional framework of the education system, and the additional cost of mitigating them, were too great to justify further consideration of a voucher system, as a means of increasing parental choice and influence.

For these reasons, the idea of vouchers is no longer on the agenda (Hansard House of Commons 22 June 1984 Vol 62 Col 290W).

The decision to abandon vouchers angered the government's right-wing supporters, and Thatcher herself was unwilling to let the idea drop, telling Channel 4 in July 1985: 'I am very disappointed that we were not able to do the voucher scheme; I think I must have another go' (quoted in Chitty 1989:187).

1980 Education Act

The 1980 Education Act (3 April) began the process of giving more power to parents. In addition to introducing the Assisted Places Scheme, it required school governing bodies to include at least two parents (Section 2(5)) and gave parents the right to choose their child's school (6) and to appeal if they were not offered the school they had chosen (7).

It also laid down new rules regarding school attendance orders (10 and 11), the creation of new schools and the closing of existing ones (12), and the number of school places (15). It ended local authorities' obligation to provide free milk and meals, except for children whose parents were in receipt of Supplementary Benefit or Family Income Supplement (22); and it allowed local authorities to establish nursery schools (24).

1981 Education Act

Parents were also given new rights in the 1981 Education Act (30 October) which incorporated some of the proposals of the 1978 Warnock Report Special Educational Needs.

Local education authorities (LEAs) were required to identify the needs of children with learning difficulties (Section 4); have assessment procedures in place for ascertaining those needs (5-6); and produce 'statements' specifying how the needs would be met (7).

The Act, however, was severely limited by the government's commitment to budget-cutting: it 'did the bare minimum to provide a new legal framework for special education, without spending any extra money at all' (Rowan 1988:98).

Warnock had identified three areas for priority action: provision for children under 5 with special educational needs; provision for young people over 16 with special needs; and teacher training. But, as Patricia Rowan pointed out:

None of these 'three areas of first priority' was to figure to any significant extent in the legislation which eventually followed, ... nor yet could subsequent changes in provision or policy be taken as unequivocal signs that the government was taking on board the spirit of Warnock. Far from it. Department of Education and Science ministers were also to spend some time and energy ducking and weaving to avoid giving parents the rights of appeal and access to information recommended in the Report; dodging the issue on the proposal for a named person who might provide a point of contact at critical times to guide parents and handicapped young people through a confusing maze of services; side-stepping the implications of recommendations designed to promote better relationships and coordination between professionals and services, and to sort out the overlapping and sometimes competing responsibilities of education and social services and of area health authorities (Rowan 1988:97-8).

In a guide to the Act published by the Advisory Centre for Education, Peter Newell argued that:

The new law on special education is a hesitant step along the road to providing adequate safeguards, rights and duties for all those involved in the education of children with special educational needs, and to ensuring their right to integration into the life and work of the community, and its 'ordinary' institutions.

It is a pale reflection of similar legislation already in force in other countries (for instance the Education of all Handicapped Children Act in the US) (quoted in Rowan 1988:100).

The curriculum

Chitty argues that the period from 1981 to 1986 was

notable for increasing central influence on the curriculum of a frankly party political nature. Statements were made by ministers and others which would have been considered quite improper in earlier periods (Chitty 1989:150).

Keith Joseph, for example, told the annual convention of the Institute of Directors in March 1982 that 'schools should preach the moral virtue of free enterprise and the pursuit of profit' (The Times Educational Supplement 26 March 1982 quoted in Chitty 1989:151).

It was 'a curious speech' from a politician who 'claimed to condemn all forms of political indoctrination in schools' (Chitty 1989:151). Joseph was apparently happy for schools to preach moral virtues as long as he approved of them. He was certainly not happy for children to be taught 'peace studies', a topic which was growing in popularity in secondary schools. In March 1984, he told a conference organised by the National Council of Women of Great Britain:

I deplore attempts to trivialise the substance of the issue of peace and war, to cloud it with inappropriate appeals to emotion, and to present it so one-sidedly that the teacher is guilty of indoctrination (DES Press Release 3 March 1982 quoted in Chitty 1989:152).

Instead, schools would be encouraged to make use of the pamphlet A Balanced View, which set out the government's case for retaining nuclear weapons.

Publicly, the DES continued to maintain that the content of the curriculum was a matter for schools and local authorities. Privately, however, DES officials were anxious to achieve greater control of the school curriculum, as Stewart Ranson made clear in his contribution to Patricia Broadfoot's 1984 book Selection Certification and Control. He argued that

The driving force for change ... has not been an external source of influence but the DES itself. The policy of reconstructing the education service has been led by the Department who have championed the initiative of strengthening the ties between school and work, between education and training in order to improve the vocational preparation of the 14-19 age group. Restructuring would require complex changes to key components of the education system: institutions would have to be rationalised, finance redirected and, critically, the curriculum and examinations would need to be recast (Ranson 1984:223-4).

He quoted from some revealing interviews with DES officials, conducted by the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) between 1979 and 1982 as part of its Research into Central-Local Relations.

One senior official commented:

our focus must be on the strategic questions of the content, shape and purposes of the whole educational system and absolutely central to that is the curriculum. We would like legislative powers over the curriculum and the powers to control the exam system by ending all those independent charters of the exam bodies (quoted in Ranson 1984:224).

Another said:

there is a need especially in the 16-19 area, for a centrally formulated approach to education: we need what the Germans call 'instrumentarium' through which Ministers can implement and operate policy ...

I see a return to centralisation of a different kind with the centre seeking to determine what goes on in institutions: this is a more fundamental centralisation than we have seen before (quoted in Ranson 1984:238).

And yet another declared that:

we are in a period of considerable social change. There may be social unrest, but we can cope with the Toxteths [a reference to a major riot in 1981]. But if we have a highly educated and idle population we may possibly anticipate more serious social conflict. People must be educated once more to know their place (quoted in Ranson 1984:241).

The 'Great Debate' about the nature and purposes of education, initiated by Labour Prime Minister Jim Callaghan in his 1976 Ruskin College speech, continued under the Conservative government with numerous pamphlets on the school curriculum from the DES, HMI, and the Schools Council.

The DES published its Report on the Circular 14/77 Review (1979), A framework for the school curriculum (1980), and The School Curriculum (1981), followed by Circular 6/81.

HMI issued A View of the Curriculum (1980) and two further 'Red Books': Curriculum 11-16: a review of progress (1981) and Curriculum 11-16: Towards a Statement of Entitlement (1983).

The Schools Council's contribution to the debate was The practical curriculum (Working Paper 70, 1981).

DES publications

Report on the Circular 14/77 Review

Circular 14/77 Local Authority Arrangements for the School Curriculum had been issued in November 1977 by Labour education secretary Shirley Williams. Local authorities were to report to her by June 1978, and she planned to publish a review of the responses.

Following the change of government, the Report on the Circular 14/77 Review was published by the DES in November 1979. In their Foreword, the Secretaries of State (for Education and Science and for Wales) described it as 'a significant document' (DES/Welsh Office 1979:iii).

It began by recording the appreciation of the education departments for the 'effort devoted by authorities to preparing their replies, some of which were very detailed and supplemented by considerable background material' (DES/Welsh Office 1979:2).

The summary of the replies, it said, showed that there were

substantial variations within the educational system in England and Wales in policies towards the curriculum. It also gives valuable insight into the ways in which authorities' curricular responsibilities are discharged (DES/Welsh Office 1979:2).

The Report stressed the importance of

the relationships between all the parties with responsibilities for school education: central and local government, school governing bodies and teachers (DES/Welsh Office 1979:2)

and added that there was no intention

to alter the existing statutory relationship between these various partners (DES/Welsh Office 1979:2).

However, the Secretaries of State concluded that the time was ripe to 'seek a measure of general agreement' (DES/Welsh Office 1979:6).

The summary of responses to Circular 14/77 suggests that not all authorities have a clear view of the desirable structure of the school curriculum, especially its core elements. They believe they should seek to give a lead in the process of reaching a national consensus on a desirable framework for the curriculum and consider the development of such a framework a priority for the education service (DES/Welsh Office 1979:6-7).

HMI had already been asked 'to formulate a view of a possible curriculum on the basis of their knowledge of schools' (DES/Welsh Office 1979:7) and the education departments would now

draw up and circulate a draft policy document suggesting the form a framework for the curriculum might take and the ground it should cover (DES/Welsh Office 1979:7).

The document would provide a basis for consultations 'within and beyond the education service' (DES/Welsh Office 1979:7) which would take place early in 1980.

The Review 'envisaged a leadership role for the Secretaries of State within a context of shared responsibilities' (Chitty 1989:143): there was no question at this stage of the DES discarding the partnership model. It was central government's role to

bring together the partners in the education service and the interests of the community at large; and with them seek an agreed view of the school curriculum which would take account of the range of local needs and allow for local developments, drawing upon the varied skills and experience which all those concerned with the service can contribute (DES/Welsh Office 1979:3).

The partnership model continued to be promoted by the DES for two more years - it can be seen in A framework for the school curriculum (1980) and in The School Curriculum (1981) - and was still evident in the 1985 White Paper Better Schools, which declared that

it would not in the view of the Government be right for the Secretaries of State's policy for the range and pattern of the 5-16 curriculum to amount to the determination of national syllabuses for that period (DES 1985:11).

A framework for the school curriculum

The Circular 14/77 Review was followed in January 1980 by A framework for the school curriculum, a DES/Welsh Office booklet which argued that each education authority 'should have a clear and known policy for the curriculum offered in its schools' (DES/Welsh Office 1980:2). Authorities needed to consider

the educational aims which the school curriculum should seek to match; the responsibility of individual schools to articulate their own aims and assess the extent to which they are being achieved; the extent to which some key subjects should be regarded as essential components of the curriculum for all pupils; and ways in which the curriculum, whatever subject structure may be adopted, should seek to prepare pupils for employment and adult responsibilities in society and to provide a sound basis for continued education (DES/Welsh Office 1980:2).

The booklet argued that

The school curriculum is not, and should not be, either static over time or rigidly uniform throughout the country. It must continually evolve to reflect changes in social attitudes and values, new economic circumstances and employment patterns, improvements in our understanding of the learning process and educational technology, and the extension of knowledge (DES/Welsh Office 1980:4).

However,

the diversity of practice that has emerged in recent years, as shown particularly by HM Inspectors' national surveys of primary and secondary schools, makes it timely to prepare guidance on the place which certain key elements of the curriculum should have in the experience of every pupil during the compulsory period of education (DES/Welsh Office 1980:5).

The booklet noted that there had been

a good deal of support ... for the idea of identifying a 'core' or essential part of the curriculum which should be followed by all pupils according to their ability. Such a core, it is hoped, would ensure that all pupils, whatever else they do, at least get a sufficient grounding in the knowledge and skills which by common consent should form part of the equipment of the educated adult (DES/Welsh Office 1980:5).

In the view of the Secretaries of State, the core should consist of English, mathematics and science; for most pupils it would also include a modern foreign language and physical education. The syllabus for religious education should be 'reconsidered from time to time in the light of the religious and cultural diversity of the society, locally and nationally, in which pupils are growing up' (DES/Welsh Office 1980:7).

Finally, the booklet noted that 'schools contribute to the preparation of young people for all aspects of adult life', and that this required 'many additions to the core subjects' (DES/Welsh Office 1980:8). These would include

areas such as craft, design and technology; the arts, including music and drama; history and geography (either as separate subjects or as components in a programme of environmental and social education); moral education, health education, preparation for parenthood and an adult role in family life; careers education and vocational guidance; and preparation for a participatory role in adult society (DES/Welsh Office 1980:8).

The time and emphasis given to these subjects might vary from school to school, but 'at one stage or another, all should find a place in the education of every pupil' (DES/Welsh Office 1980:8).

The School Curriculum

The partnership model of curriculum responsibility was endorsed once again - though this time with some caveats - in another DES/Welsh Office booklet, The School Curriculum, published on 25 March 1981.

It argued that the 5-16 curriculum 'cannot, and should not, remain static, but must respond to the changing demands made by the world outside the school' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:1). This was a challenging task which many schools were tackling with success. However, evidence from HMI surveys had revealed 'some serious weaknesses which require present practice to be substantially modified' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:2).

This calls not for a change in the statutory framework of the education service but for a reappraisal of how each partner in the service should now discharge those responsibilities assigned to him by law. The Secretaries of State consider that curriculum policies should be developed and implemented on the basis of the existing statutory relationship between the partners and that this process must be based upon a clear understanding of, and must pay proper regard to, the responsibilities and interests of each partner and the contribution that each can make (DES/Welsh Office 1981:2).

In order to fulfil their role in this partnership, the Secretaries of State (for Education and Science and for Wales) had decided to 'set out in some detail the approach to the school curriculum which they consider should now be followed in the years ahead' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:5).

In the light of the general guidance in this paper the Secretaries of State now believe that every local education authority should frame policies for the school curriculum and plan the deployment of the available resources to that end; and that every school should analyse its aims, set these out in writing, and regularly assess how far the curriculum within the school as a whole and for individual pupils measures up to these aims (DES/Welsh Office 1981:5).

The Secretaries of State acknowledged that the curriculum could be 'described and analysed in several ways, each of which has its advantages and limitations' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:6). They set out their guidance in terms of subjects, but agreed that

other frames of reference are also required. These may be in terms of the skills required at particular stages of a pupil's career; or of areas of experience such as the eight used in HM Inspectors' working papers on the 11-16 curriculum: the aesthetic and creative, the ethical, the linguistic, the mathematical, the physical, the scientific, the social and political, and the spiritual (DES/Welsh Office 1981:6).

They argued that 'What is taught in schools, and the way it is taught, must appropriately reflect fundamental values in our society' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:6). In this context, three issues deserved special mention: first, that society had become multicultural; second, that the increasing use of technology required greater adaptability, self-reliance and other personal qualities; and third, that sexual equality needed to be supported in the curriculum: 'It is essential to ensure that equal curricular opportunity is genuinely available to both boys and girls' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:7).

The curriculum needed 'to be viewed as a whole and to take account of different needs and abilities: to be concerned not only with what is to be learned but also with how it is to be learned' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:8).

The aims of primary education - 'to extend children's knowledge of themselves and of the world in which they live ... to develop skills and concepts, to help them relate to others, and to encourage a proper self-confidence' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:10) - could not be identified with separate subject areas, nor could set amounts of time be assigned to the various elements.

Primary schools, said the Secretaries of State, rightly attached a high priority to English and maths: this was 'an overriding responsibility' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:10). Topic work should be well planned and there should be 'more effective science teaching' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:11). The experiments in teaching a foreign language in primary schools had had 'mixed results' and should be continued only where there was adequate teacher expertise.

With regard to secondary schools, the Secretaries of State emphasised three propositions:

1. Schools should plan their curriculum as a whole. The curriculum offered by a school, and the curriculum received by individual pupils, should not be simply a collection of separate subjects; nor is it sufficient to transfer, with modifications, the ideas about the curriculum in the separate selective and non-selective schools of an earlier generation into the comprehensive schools attended by most pupils today.

2. There is an overwhelming case for providing all pupils between 11 and 16 with curricula of a broadly common character, designed so as to ensure a balanced education during this period and in order to prevent subsequent choices being needlessly restricted.

3. School education needs to equip young people fully for adult and working life in a world which is changing very rapidly indeed, particularly in consequence of new technological developments: they must be able to see where their education has meaning outside school (DES/Welsh Office 1981:12-13).

The pamphlet then discussed the place of English, maths, science and modern languages in the secondary curriculum. It noted that 'many aspects of adult life and work are likely to be transformed by developments in computer science and in information and control technology' and argued that it was therefore 'important that pupils should become familiar with the use and application of computers' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:17). Craft, design and technology was 'part of the preparation for living and working in modern industrial society' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:17).

Finally, three points were made regarding preparation for adult life. First, 'the curriculum needs to be related to what happens outside schools' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:18); there should therefore be a greater emphasis on practical work and economic understanding. Second, 'Pupils need better and more systematic careers education and guidance'. And third, 'An increasing number of local education authorities and schools have recognised the importance of establishing links between the education service and industry' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:18): this was an area the Secretaries of State wished to see expanded.

In its concluding section, The Way Forward, the pamphlet welcomed the work which had already been undertaken by schools and local authorities 'often as the result of sustained effort and experiment over the years' and acknowledged that 'Further progress will similarly be gradual and will be affected by the availability of teachers and other resources' (DES/Welsh Office 1981:19).

Circular 6/81

Circular 6/81 The School Curriculum, issued by the DES on 1 October 1981, asked each local education authority to

(a) review its policy for the school curriculum in its area, and its arrangements for making that policy known to all concerned;

(b) review the extent to which current provision in the schools is consistent with that policy; and

(c) plan future developments accordingly, within the resources available (DES 1981: para 5).

In taking these actions, local education authorities were to consult governors, teachers, and others concerned with the schools.

The School Curriculum was criticised in the educational press for its interventionist stance, but there were also concerns that the curriculum proposals put forward by both the DES and HMI seemed to be having little effect in practice. 'Evidence reaching the Department, both from HMI and in response to Circular 14/77 pointed to a disconcerting inertia on the part of many local authorities and schools' (Chitty 1989:144).

As a result, DES bureaucrats 'tired of the politics of persuasion' (Chitty 1989:145) and the Department ceased publishing documents on the curriculum in 1981. Instead, the government sought greater control of the curriculum by other means, including

- vetting the criteria for the new General Certificate of Secondary Education;

- abolishing the teacher-dominated Schools Council (1984);

- establishing the Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education (CATE); and

- controlling teachers' in-service training by means of specific grants (see Better Schools DES 1985:54).

HMI publications

A View of the Curriculum

A View of the Curriculum (1980), was the eleventh in the HMI series Matters for Discussion.

It began with a definition of the school curriculum:

The curriculum in its full sense comprises all the opportunities for learning provided by a school. It includes the formal programme of lessons in the timetable: the so - called 'extracurricular' and 'out of school' activities deliberately promoted or supported by the school; and the climate of relationships, attitudes, styles of behaviour and the general quality of life established in the school community as a whole (HMI 1980a:1).

It noted the 'necessary tension between common and individual needs' (HMI 1980a:1) and argued that, 'If it is to be effective, the school curriculum must allow for differences' (HMI 1980a:2).

In the primary school, all children needed a programme which would enable them

to engage with other children and with adults in a variety of working and social relationships;

to increase their range and understanding of English, and particularly to develop their ability and inclination to read and write for information and imaginative stimulation;

to acquire better physical control when they are writing, or exercising utilitarian skills and engaging in imaginative expression in art, craft, music, drama or movement generally (HMI 1980a:7).

HMI stressed the importance of developing a wide range of skills, 'not least those concerned with the development of good personal relations', which were 'learnt in the context of developing concepts and in the acquisition of information' (HMI 1980a:10).

In relation to secondary schools, HMI put forward 14 'propositions for consideration' (HMI 1980a:14-18). They argued:

- that an explicit national consensus was needed on what constituted five years of secondary education;

- that there should be 'comparable opportunities and comparable quality, though not uniformity' for all pupils in all schools (HMI 1980a:14);

- that science should take its place alongside English, maths, religious and physical education as key elements of the curriculum; and

- that in a common curriculum there should 'still be room and need for differentiation and choice' (HMI 1980a:18).

A View of the Curriculum concluded that

In the end, whatever is decided nationally must leave much for individual local education authorities and schools to determine as they interpret the national agreement to take account of the nature of individual schools and individual pupils. It must take account of children's capacity to learn at any given stage of their maturity and identify what is intrinsically worth learning and best acquired through schooling. It must, too, allow for future modification in response to new needs in the world outside schools: decisions cannot sensibly be taken once and for all. The effort involved will be justified if it leads to developing more fully the potential of all children (HMI 1980a:23).

Red Books 2 and 3

HMI also produced two more 'Red Books' (the first had been published in 1977 - see the previous chapter), describing progress with curriculum development projects involving 41 schools in five local authorities.

Red Book 2 Curriculum 11-16: a Review of Progress (1981) was 'not a contribution by HMI to discussion about the theoretical basis of the curriculum' but was concerned with 'the reality of the curriculum for real pupils in real schools'. It advocated 'no models of product or process' but made clear that 'time, good order and shared commitment are essential to successful evaluation and change, which may have to be achieved small step by small step' (HMI 1981:v).

Red Book 3 Curriculum 11-16: Towards a Statement of Entitlement (1983) contained the final report on the projects. The aim, it said, had been

to establish a working relationship which would help the schools involved to examine, rethink and improve their curricula and classroom practice. The focus of everyone's effort, which might be shared by every secondary school in the country, was to find better ways of meeting the needs of all their pupils in the rapidly changing circumstances of today (HMI 1983a:v).

The conclusion was that 'any adequate specification of the curriculum to which all pupils are entitled up to 16 should include the following' (HMI 1983a:26):

i a statement of aims relating to the education of the individuals and to the preparation of young people for life after school;

ii a statement of objectives in terms of skills, attitudes, concepts and knowledge;

iii a balanced allocation of time for all the eight areas of experience (the aesthetic and creative; the ethical; the linguistic; the mathematical; the physical; the scientific; the social and political; and the spiritual) which reflects the importance of each and a judgement of how the various component courses contribute to these areas;

iv provision for the entitlement curriculum in all five years for all pupils of 70-80 per cent of the time available with the remaining time for various other components to be taken by pupils according to their individual talents and interests;

v methods of teaching and learning which ensure the progressive acquisition by pupils of the desired skills, attitudes, concepts and knowledge;

vi a policy for staffing and resource allocation which is based on the curriculum;

vii acceptance of the need for assessment which monitors pupils' progress in learning, and for explicit procedures, accessible to the public, which reflect and reinforce i. to v. above (HMI 1983a:26-7).

Schools Council contribution

The practical curriculum

The Schools Council's contribution to the Great Debate was The practical curriculum (Working Paper 70), published in 1981.

The booklet was not, the authors said, about subjects or content, but about the process of curriculum development. They hoped they had 'found a way of presenting the curriculum as an activity and not merely a syllabus or an exhortation' (Schools Council 1981:7). Their report was 'not intended to be either definitive or prescriptive' but to 'provoke discussion and provide new insights' (Schools Council 1981:7).

The Schools Council, they suggested, had a distinctive contribution to make because

It is the only national forum where representatives of central government, local authorities, teachers' organisations, further education and higher education, employers, trade unions, parents, churches and examining bodies meet to discuss the content and process of education in school (Schools Council 1981:9).

The first chapter, A rationale for the curriculum, began with some underlying principles of curriculum development and listed six central issues:

i the overwhelming need, for each school and for the country as a whole, is to find a rationale for the curriculum now every child has a right to eleven years' education;

ii then to identify the irreducible minimum to which every pupil should have a right of access; the Council believes this minimum should reflect the complex diversity of human nature and the capacity schools have to contribute to every aspect of personal and social growth. The minimum curriculum should be broad and stimulating;

iii to decide what mix of subject disciplines and kinds of experience a school should provide to meet the diverse needs of its pupils, and to achieve a reasonable balance over the eleven years of compulsory schooling;

iv to take account of the implications of having externally examined outcomes for most pupils;

v to negotiate a match between the desired curriculum and the staff, accommodation, equipment and materials available; and

vi to think out ways of discovering whether the planned curriculum achieves what is hoped of it (Schools Council 1981:14).

Later chapters dealt with planning and monitoring the curriculum, and assessment.

The authors hoped the handbook would be 'a useful basis for workshops and seminars on planning the curriculum. It might also be helpful in local evaluative or case studies' (Schools Council 1981:67).

It had been suggested, they noted, that the Council could usefully prepare 'more detailed statements about objectives and skills, for different age groups and different subjects' and try to identify 'exactly what knowledge and skills the study of traditional subjects develops'. Both tasks seemed 'appropriate for the Council' (Schools Council 1981:67).

Inside the primary classroom

One other publication is worth noting here. Inside the primary classroom by Maurice Galton, Brian Simon and Paul Croll, published in 1980, was part of the Observational Research and Classroom Learning Evaluation (ORACLE) project, funded by the Social Science Research Council between 1975 and 1980.

Inside the primary classroom reported the findings of 'the first large-scale observational study of primary school classrooms to be undertaken in this country'. It presented 'an over-all analysis of pupil and teacher activity' and identified 'different patterns of teacher and pupil behaviour'. Its findings were 'directly relevant to the criticisms of new approaches in the primary school': they provided 'a mass of objective data against which these criticisms may be evaluated' (Galton, Simon and Croll 1980:1).

Youth Training Scheme

Employers and politicians had long argued that the curriculum of schools and colleges should be more closely focused on preparing pupils to meet the needs of industry, a view which was certainly shared by the Thatcher governments.

The Department of Employment's 1981 White Paper A New Training Initiative: A Programme for Action, published in December, noted that increasing numbers of students were taking full-time vocational courses which combined 'the theory and practice of particular occupational skills with general education in subjects which have hitherto been studied mainly part-time' (Department of Employment 1981:5).

It argued that there was a need for 'vocationally-orientated courses of a more general kind' (Department of Employment 1981:6) and it proposed replacing the Youth Opportunities Programme, which had been introduced in 1978, with 'a new and better Youth Training Scheme' to be run by the Manpower Services Commission. It would 'cover all unemployed minimum age school-leavers by September 1983' (Department of Employment 1981:7).

There would be five main elements:

- induction and assessment;

- basic skills including numeracy, literacy, communication, and practical competence;

- occupationally relevant education and training for personal development in a variety of working contexts;

- guidance and counselling; and

- record and review of progress.

The new scheme was to be 'first and last a training scheme' and this would be 'reflected in its structure, its delivery and the terms and conditions for the young trainees' (Department of Employment 1981:9).

Technical and Vocational Education Initiative

Margaret Thatcher announced the Technical and Vocational Education Initiative (TVEI) in a House of Commons statement on 12 November 1982. In reply to a question from Sir William van Straubenzee, she said:

Growing concern about existing arrangements has been expressed over many years, not least by the National Economic Development Council. I have asked the chairman of the Manpower Services Commission, together with my right hon. Friends the Secretaries of State for Education and Science, for Employment and for Wales, to develop a pilot scheme to start by September 1983, for new institutional arrangements for technical and vocational education for 14 to 18-year-olds, within existing financial resources, and, where possible, in association with local education authorities (Hansard House of Commons 12 November 1982 Vol 31 Cols 271-2W).

To accompany the announcement, the Department of Employment issued a press release (12 November 1982), stating that TVEI was designed to 'stimulate technical and vocational education for 14- to 18-year-olds as part of a drive to improve our performance in the development of new skills and technology' (quoted in Chitty 1989 173).

The Initiative had been devised by David (later Lord) Young (1932- ), Chair of the Manpower Services Commission (MSC), Keith Joseph and Norman Tebbit (1931- ) (then Secretary of State for Employment): there had been no consultations with the DES or teachers or the local authorities. The fact that it was the Prime Minister who made the announcement, rather than Young or Joseph, 'may be indicative of the importance attached to this Initiative or symptomatic of a developing rivalry between the DES and the MSC for control of education and training' (Chitty 1989:146).

On 28 January 1983, Young wrote to all local authority directors of education in England and Wales, outlining what the MSC saw as the main objectives of TVEI:

First, our general objective is to widen and enrich the curriculum in a way that will help young people to prepare for the world of work, and to develop skills and interests, including creative abilities, that will help them to lead a fuller life and to be able to contribute more to the life of the community. Secondly, we are in the business of helping students to 'learn to learn'. In a time of rapid technological change, the extent to which particular occupational skills are required will change. What is important about this Initiative is that youngsters should receive an education which will enable them to adapt to the changing occupational environment (quoted in Chitty 1989:173-4).

The notion that TVEI was intended for pupils of all ability levels angered right-wing members of the Tory party who were 'prepared to tolerate courses of a vocational nature' only if they were reserved for pupils who could be labelled as 'non-academic' or 'non-examinable' (Chitty 1989:174).

TVEI began with fourteen pilot projects in the autumn of 1983. By 1986, 85,000 students in 600 institutions were involved in four-year programmes

designed to stimulate work-related education, make the curriculum more relevant to post-school life and enable students to aim for nationally-recognised qualifications in a wide range of technical and vocational subject areas (Chitty 1989:146).

There was considerable confusion at first about responsibility for the Initiative: the MSC issued a statement inviting local education authorities 'to work in partnership with us to further advance vocational education for young people' (quoted in Chitty 1989:147). But the nature of this 'partnership' was unclear and DES officials found themselves in a difficult position as local authorities expressed concerns about

the constitutional propriety of the MSC administering and funding part of the service for which local authorities are responsible under the 1944 Act (Education 26 November 1982 quoted in Chitty 1989:148).

The Initiative 'represented a powerful challenge not only to the power of the local education authorities but also to that of the DES itself' (Chitty 1989:148). The Times Educational Supplement was remarkably hostile:

Mrs Thatcher's bombshell last Friday has given yet another hefty jolt to the kaleidoscope of relationships which determine educational policy and curriculum development. The new Chairman of the Manpower Services Commission, Mr. David Young, has only had to wait a matter of six months before initiating a new imperialistic drive downwards into the secondary school. The Prime Minister and Mr. Norman Tebbit have brushed the Department of Education and Science aside ... entrusting the planning, the direction and the finance of this major attempt to offer a new set of vocational options at around the age of 14 to Mr. Young and his colleagues ...

The Prime Minister's statement referred to 'new institutional arrangements for technical and vocational education for 14-18-year-olds within existing financial resources', and 'where possible, in association with local education authorities'. The inclusion of the words 'where possible' has sent a frisson of alarm through the local education authorities ... This alarm signal seems to have been fully intended (The Times Educational Supplement 19 November 1982 quoted in Chitty 1989:148).

In the event, TVEI proved an unsuitable vehicle for vocationalising the secondary school curriculum for 'non-academic' pupils,

largely because the term 'vocational' in the title was never clearly defined and ... there was also considerable vagueness about the Initiative's intended 'target group'. Over the years, many teachers and local authorities have tried to make the Initiative attractive to all sections of the ability range ... This helps to explain why the Initiative has incurred the hostility of leading members of the New Right (Chitty 1989:174)

Nonetheless, the Thatcher government was, for the time being, clearly proud of TVEI, describing it in glowing terms in Better Schools: