[page 128]

APPENDICES

Appendix I

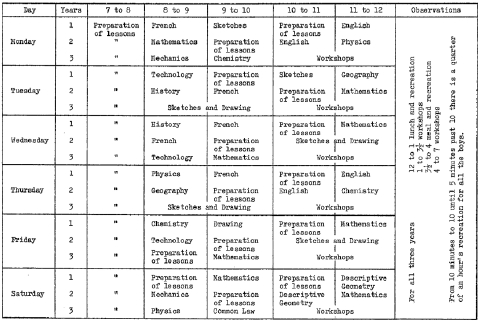

Timetable of the Paris Municipal Apprenticeship School for Boys

[click on the image for a larger version]

[click on the image for a larger version]

[page 129]

Appendix II

Institutions and towns in the UK visited by the Royal Commissioners on Technical Instruction

University of London

Kings College

Normal School of Science and Royal School of Mines, South Kensington

Museum of Practical Geology

National Art Training School

Science and Art Department

City and Guilds of London Polytechnic

Young Men's Christian Institute

Royal Indian Engineering College

Royal Naval College, Greenwich

Crystal Palace School of Engineering

Oxford

Cambridge

Manchester

Liverpool

Oldham

Barrow in Furness

Birmingham

Leeds

Sheffield

Bradford

Keighley

Nottingham

Bristol

Bedford

Kendal

Glasgow Edinburgh

Ireland (Dublin, Cork and Belfast)

[page 130]

Appendix III

Statutes at Large, 52 and 53 Vict. 1889. pp 384-388

AN ACT TO FACILITATE THE PROVISION OF TECHNICAL INSTRUCTION

30th August 1889

1 Power for local authority to supply or aid the supply of technical instruction

(1) A local authority may from time to time out of the local rate supply or aid the supply of technical or manual instruction, to such extent and on such terms as the authority think expedient, subject to the following restrictions, namely:-

(a) The local authority shall not out of the local rate supply or aid the supply of technical or manual instruction to scholars receiving instruction at an elementary school in the obligatory or standard subjects prescribed by the minutes of the Education Department for the time being in force;

(b) It shall not be required, as a condition of any scholar being admitted into or continuing in any school aided out of the local rate, and receiving technical or manual instruction under this Act that he shall attend at or abstain from attending any Sunday school or any place of religious worship, or that he shall attend any religious observance or any instruction in religious subjects in the school or elsewhere: Provided that in any school, the erection of which has been aided under this Act, it shall not be required, as a condition of any scholar being admitted into or continuing in such school, that he shall attend at or abstain from attending any Sunday school or any place of religious worship, or that he shall attend any religious observance or any instruction in religious subjects in the school or elsewhere;

(c) No religious catechism or religious formulary, which is distinctive of any particular denomination, shall be taught at any school aided out of the local rate, to a scholar attending only for the purposes of technical or manual instruction under this Act, and the times for prayer or religious worship, or for any lesson or series of lessons on a religious subject, shall be conveniently arranged for the purpose of allowing the withdrawal of such scholar therefrom;

(d) A local authority may, on the request of the school board for its district or any part of its district, or of any other managers of a school or institution within its district, for the time being in receipt of aid from the Department of Science and Art, make, out of any local rate raised in pursuance of this Act, to such extent as may be reasonably sufficient, having regard to the requirements of the district, but subject to the conditions and restrictions contained in this section, provision in aid of the technical and manual instruction for the time being supplied in schools or institutions within its

[page 131]

district, and shall distribute the provision so made in proportion to the nature and amount of efficient technical or manual instruction supplied by those schools or institutions respectively;

(e) Where such other managers of a school or institution receive aid from a local authority in pursuance of this section, the local authority shall, for the purposes of this Act, be represented on the governing body of the school or institution in such proportion as will, as nearly as may be, correspond to the proportion which the aid given by the local authority bears to the contribution made from all sources other than the local rate and money provided by Parliament to the cost of the technical or manual instruction given in the school or institution aided;

(f) If any question arises as to the sufficiency of the provision made under this section, or as to the qualification of any school or institution to participate in any such provision, or as to the amount to be allotted to each school or institution, or as to the extent to which, or mode in which, the local authority is to be represented on the governing body of any such school or institution, the question shall be determined by the Department of Science and Art: Provided that no such provision, out of any rate raised in pursuance of this Act, shall be made in aid of technical or manual instruction in any school conducted for private profit; and

(g) The amount of the rate to be raised in any one year by a local authority for the purposes of this Act shall not exceed the sum of one penny in the pound.

(2) A local authority may for the purposes of this Act appoint a committee consisting either wholly or partly of members of the local authority, and may delegate to any such committee any powers exercisable by the authority under this Act, except the power of raising a rate or borrowing money.

(3) Nothing in this Act shall be construed so as to interfere with any existing powers of school boards with respect to the provision of technical and manual instruction.

2 Provision for entrance examination

It shall be competent for any school board or local authority, should they think fit, to institute an entrance examination for persons desirous of attending technical schools or classes under their management or to which they contribute.

3 Parliamentary grants in aid of technical instruction

The conditions on which parliamentary grants may be made in aid of technical or manual instruction shall be those contained in the minutes of the Department of Science and Art in force for the time being.

[page 132]

4 Provisions as to local authorities

(1) For the purposes of this Act the expression "local authority" shall mean the council of any county or borough, and any urban sanitary authority within the meaning of the Public Health Acts.

(2) The local rate for the purposes of this Act shall be-

(a) In the case of a county council, the county fund;

(b) In the case of a borough council, the borough fund or borough rate;

(c) In the case of an urban sanitary authority not being a borough council, the district fund and general district rate, or other fund or rate applicable to the general purposes of the Public Health Acts;

(3) A county council may charge any expenses incurred by them under this Act on any part of their county for the requirements of which such expenses have been incurred.

(4) A local authority may borrow for the purposes of this Act -

(a) In the case of a county council, in manner provided by the Local Government Act 1888 (51 & 52 Vict. c. 41):

(b) In the case of a borough council, as if the purposes of this Act were purposes for which they are authorised by section one hundred and six of the Municipal Corporations Act 1882 (45 & 46 Vict. c. 50), to borrow:

(c) In the case of an urban sanitary authority not being a borough council, as if the purposes of this Act were purposes for which they are authorised to borrow under the Public Health Acts.

5 Audit of accounts of aided schools

Where the managers of a school or institution receive aid from a local authority in pursuance of this Act, they shall render to the local authority such accounts relating to the application of the money granted in aid, and those accounts shall be verified and audited in such manner as the local authority may require, and the managers shall be personally liable to refund to the local authority any money granted under this Act, and not shown to be properly applied for the purposes for which it was granted.

6 Audit of accounts of urban sanitary authority

The accounts of the receipts and expenditure of an urban sanitary authority under this Act shall be audited in like manner and with the like incidents and consequences, as the accounts of their receipts and expenditure under the Public Health Act 1875.

7 (Relates specifically to Ireland)

[page 133]

8 Meaning of technical and manual instruction

In this Act -

The expression "technical instruction" shall mean instruction in the principles of science and art applicable to industries, and in the application of special branches of science and art to specific industries or employments. It shall not include teaching the practice of any trade or industry or employment, but, save as aforesaid, shall include instruction in the branches of science and art with respect to which grants are for the time being made by the Department of Science and Art, and any other form of instruction (including modern languages and commercial and agricultural subjects), which may for the time being be sanctioned by that Department by a minute laid before Parliament and made on the representation of a local authority that such a form of instruction is required by the circumstances of its district.

The expression "manual instruction" shall mean instruction in the use of tools, processes of agriculture, and modelling in clay, wood, or other material.

9 Extent of Act

This Act shall not extend to Scotland.

10 Short title

This Act may be cited as the Technical Instruction Act 1889.

[page 134]

Appendix IV

Census return 1901

Analysis of the figures relating to the employment of the inhabitants in the County of Middlesex. Figures apply to all persons of both sexes of 10 years of age and upwards engaged in the different classes of employment.

| Class of Occupation | Males | Females | Total |

| Domestic | 8180 | 59736 | 67916 |

| Building Trades | 36670 | 14 | 36684 |

| Conveyance | 31515 | 483 | 31998 |

| Commercial | 27006 | 3101 | 30107 |

| Food and Lodging | 20605 | 4736 | 25368 |

| Professional | 11792 | 9970 | 21762 |

| Dress | 6930 | 13708 | 20638 |

| Miscellaneous work | 17609 | 1190 | 18799 |

| Metals and Machines | 14143 | 189 | 14332 |

| Agriculture and Horticulture | 12022 | 706 | 12728 |

| Paper, printing, etc | 6983 | 1456 | 8439 |

| Precious metals | 5679 | 754 | 6433 |

| Wood, furniture etc | 5847 | 335 | 6182 |

| Textiles, fabrics, etc | 3310 | 2706 | 6016 |

| Chemicals | 2772 | 932 | 3704 |

| Brick, Glass, etc | 2013 | 114 | 2172 |

| Gas, water and electricity | 2093 | 1 | 2094 |

| Skin and leather | 1550 | 271 | 1821 |

| Various | 9385 | 1067 | 10452 |

Figures taken from Middlesex Technical Education Committee Minute Book 14, p 182

[page 135]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. MS Primary Sources

Greater London Record Office, Middlesex Section:

Middlesex County Council Minutes, Vols 1-22, 1889-1902

Middlesex County Council Technical Education Committee Minutes, Vols 1-15, 1892-1903

Middlesex County Council Education Committee Minutes, Vol 1, June-December 1903

2. Printed Primary Sources

(a) Greater London Record Office, Middlesex Section:

Middlesex County Council Education Committee Minutes, Vol. 21, 1920

Middlesex County Yearbooks, 1891-1902

National Association for the Promotion of Technical and Secondary Education in England and Wales Yearbooks, 1892-1903

(b) House of Lords Records Office:

Report of the Samuelson Inquiry Commissioners on Technical Education, 1867, PP 1867, Vol 20

Reports of the Royal Commissioners on Technical Instruction, PP 1882, Vol 27, and PP 1884, Vols 29-31

Technical Instruction Act, Statutes at Large, 52 and 53 Vict., 1889

An Act to Amend the Law Relating to Technical Instruction, Statutes at Large, 55 Vict., 1891

Local Taxation (Customs and Excise Act), Statutes at Large, 53 and 54 Vict., 1890

[page 136]

(c) British Museum Newspaper Library:

The Times, 13th October 1851 and 16th May 1884

Middlesex County Times, 21st January 1928

(d) Polytechnic of Central London Library:

Magnus, P, Educational Aims and Efforts, London: 1910

Magnus, P, Industrial Education, London: Keegan Paul, Trench & Co., 1888

Wood, E M, Quintin Hogg, A Biography, London: Nisbet & Co., 1904

3. Secondary Sources

Books

Argles , M, South Kensington to Robbins, London: Green & Co., 1964

Ashby, E, Education for an Age of Technology, in Singer, C, et al, A History of Technology, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1958

Bagley, J J and A J, The State and Education in England and Wales, 1833-1968, London: Macmillan, 1969

Cardwell, D S L, The Organisation of Science in England, London: Heinemann, 1922 (revised edition)

Foden, F, Philip Magnus, Victorian Educational Pioneer, London: Valentine Mitchell, 1970

Hobsbawm, Industry and Empire, London: Penguin, 1977, (revised edition)

Jackson, A A, Semi Detached London, London, George Allan & Unwin, 1973

Maclure, J S, Educational Documents, England and Wales, 1816 to the Present Day, London: Methuen, 1973, (revised edition)

Millis, C T, Technical Education: Its Aims and Development, London: Edward Arnold & Co., 1925

Radcliffe, C, Middlesex, London: Evans Brothers Ltd., 1939

[page 137]

Robbins, M, Middlesex, London: Collins, 1953

Saul, S B, The Myth of the Great Depression, 1873-1896, London: Macmillan, 1969

Taylor, A J, Laissez-faire and State Intervention in Nineteenth-Century Britain, London: Macmillan, 1972

Van der Eyken, W, Education, The Child and Society, London: Penguin, 1973

Wood, A, Nineteenth Century Britain, 1815-1914, London: Longman, 1973 (revised edition)

Wood, E M, A History of the Polytechnic, London: Macdonald, 1965

Articles, Journals, Periodicals, etc.

(a) Published

Argles, M, "The Royal Commission on Technical Instruction, 1881-1884, Its Inception and Composition", in The Vocational Aspect of Secondary and Further Education, Vol XI, No 23, 1959, pp 97-104

Gowing, M, "Science, Technology and Education: England in 1870", in Records of the Royal Society, Vol 32, 1977

Kilburn Polytechnic Prospectus, 1977

Musgrave, P W, "Constant Factors in the Demand for Technical Education, 1860-1960", in British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol XIV, No 2, May 1966, pp 173-87

Musgrave, P W, "The Definition of Technical Education, 1860-1910", in The Vocational Aspect of Secondary and Further Education, Vol XVI, No 34, 1964, pp 105-11

The Times Higher Education Supplement, 28th January 1977 and 9th March 1977

(b) Unpublished

Blanchet, J, Science, Craft and State, 1867-1906 (PhD thesis)

Committee of Directors of Polytechnics, Committee papers 1977, St/51

[page 138]

Old, C L, The Engineer and Society in Victorian Britain, paper presented to the Council of Engineering Institutions, 1965

(c) Oral evidence

Interview with Mr J T Fielding, 18th and 19th June 1977